The military escalations between NATO (well, the U.S., really) and Russia over Ukraine are no joke.

The price of war between two nuclear superpowers is as terrifying as it is clear.

So what is it that can get in the way of saying NO to military escalations?

What is this narrative that is simply illogical but so widespread?

A long answer: it is something I have written about extensively in my article called Russia, China, and Our Endless Cold (And Hot) Wars. Little did I know how relevant it would not only when it comes to China but now Russia!

A short answer: it is the accusations that come in a form of a false dichotomy that oftentimes follow any attempt to criticise military escalations.

The dichotomy is simple: if you criticise A, you must like B.

What does that look like?

If you don’t like the idea of AUKUS and the U.S.’ hybrid war on China, you must love everything China does.

If you say let’s not put sanctions on Iran because that means ordinary people don’t have access to medicine, you must be a fan of the Iranian government.

And if you say the U.S. shouldn’t be sending troops to Ukraine, you must like Putin.

What this narrative does, is shrinks the space where dialogue could take place, it doesn’t allow for any meaningful nuance, and makes the idea of diplomacy seem like something hostile towards the very people that it aims to protect from an outbreak of war.

So the ones who say “war is never an aswer” get portrayed as liking authoritarian regimes (because if you criticise A it means you like B, remember?) or simply not understanding the issue (because you wouldn’t be criticising A in the first place then).

Do you see how dangerous this rhetoric is?

Can you see it being used now, when the U.S. is calling for more troops in Europe?

(that is even when Ukrainians themselves are not asking for this sort of help)

In fact, the threat from Russia as it’s felt in Ukraine itself doean’t seem to be how the media in the West is presenting it:

But let’s come back to that false dichotomy.

If we’re rejecting this illogical narrative, what do we have to allow ourselves to think?

Here are some examples.

You can be against war with countries that don’t have a great human rights record.

You can be against sanctions against regimes that you don’t personally like.

And yes, you can be against military escalations when it is Putin who’s on the other side.

I must add, in this specific case, me myself being from a NATO country does add an extra layer of considerations. For example, the fact that there are a lof of people in Eastern Europe who consider the U.S. and NATO as selfless protectors of the region. When historically Russia has been a threat for so long, the desire to have a strong protector that is, well, NOT Russia, is easy to understand.

I still remember something I’ve heard a famous Lithuanian journalist say about Lithuania joining NATO, when I was still a teenager: that NATO – and the U.S. in particular – is an ally that Lithuania (as different political entities throughout the years) has been looking for for…a thousand years.

A thousand years.

How strong is this?

It’s very strong, of course, and to have a powerful ally that you see as a benevolent one must feel great.

But it only fuels that false dichotomy.

And it shouldn’t make us forget how that powerful ally has been “saving” people in different regions. How Iraq was “saved”. What happened to Afghanistan. How, with the ally’s support, people in Yemen are being saved.

In other words, if Russia is seen as having its own interests, why would we not see the U.S. and NATO as actors who also have their interests? And, knowing just the recent history, why would we ever assume that these interests are the wellbeing of Eastern Europeans?

In the end, it’s not about who’s right but which approach can prevent war.

But in this situation, we can’t even be sure that no war is the outcome that the U.S. wants.

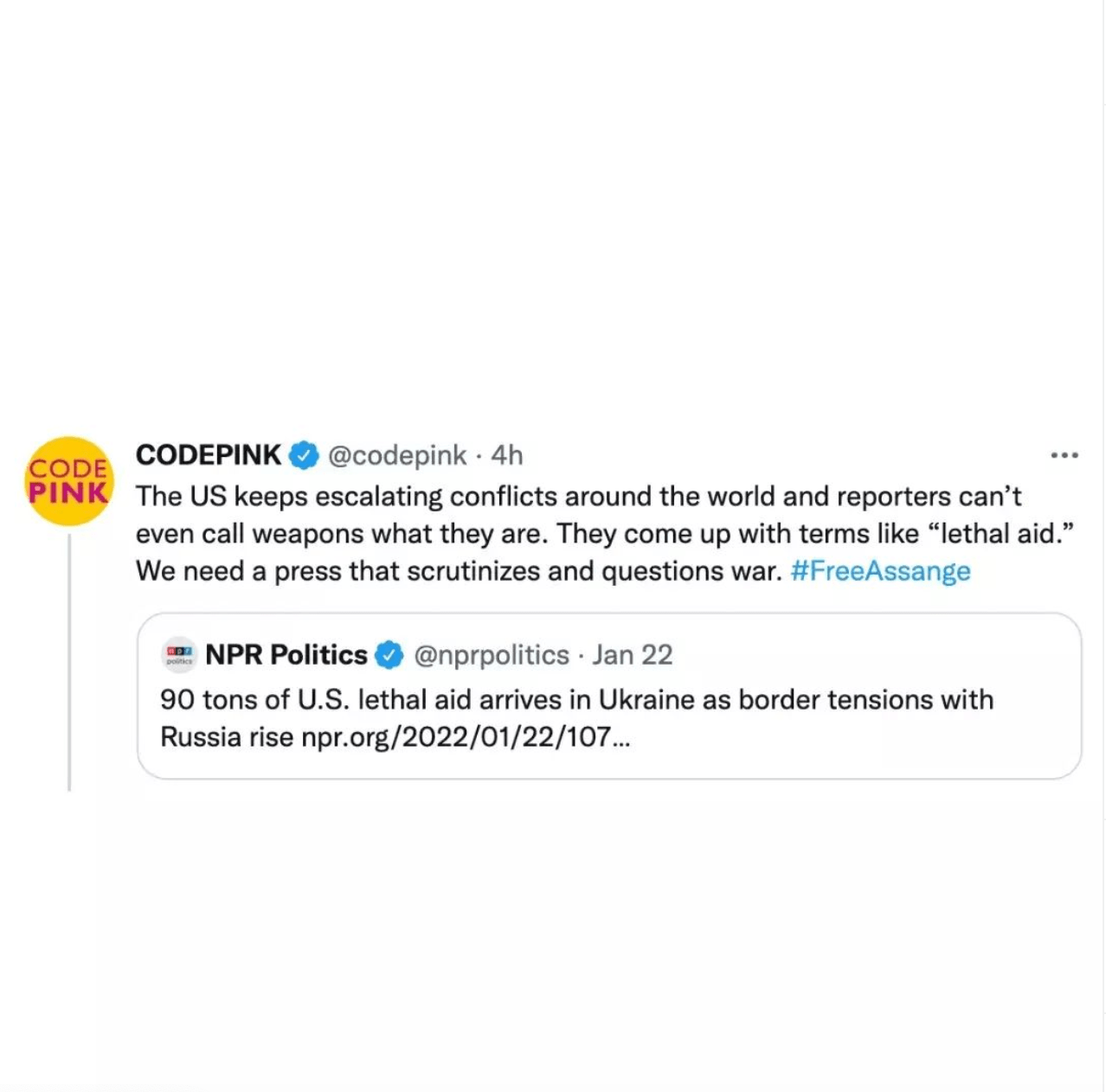

The CEO of Raytheon, a major weapons manufacturer, is getting excited to see more escalations in Eastern Europe.

We don’t have tweets from twenty years ago, but I bet this is something similar to how Afghanistan was being seen by military contractors then. According to the Costs of War project, if there is a winner in the 20-year-old war, these are surely private companies.

It would be great to see the U.S. and NATO as the selfless protectors of Eastern Europe. But you can’t unlearn how the U.S. military-industrial complex works, and you cannot unlearn the fact that people who sit on the Board of Directors of weapons manufacturers are oftentimes the same ones shaping the U.S. foreign policy.

And when war is always profitable, why would you use diplomacy?

So what does it mean to be anti-war when a war one has in mind is not a hypothetical one?

I believe it is to notice this dangerous rhetoric, to dismantle it, to refuse to participate in it, and to demand not war but diplomacy.

Latest from the Blog

How Fascist Regimes See Growing up, Standing up for People, and Writing Poems as Threats

Hind Rajab was killed by Israeli forces two years ago today – and that is one of the threads of history that I talk about in my essay-like video. It’s about fascism, its victims, the heaviness of witnessing these horrors, and how we can move forward.

On U.S. State Violence: A Continuation, Not a Rupture

The recent murder of Alex Pretti by ICE agents is one painfully clear indication – or, rather, a reminder – that in the U.S, the violence abroad has come back as fascism at home.

After Having Enabled It for Decades, The EU Is Appalled by U.S. Imperialism — Only When It Threatens Its Shores

After having enabled U.S. and Israeli military aggression around the world, notice the EU appeal to international law when the territorial integrity of Denmark is threatened by the U.S.

If You’d Like The EU to Cut Trade Ties with Israel, Here’s An Action to Take and Share

The EU leadership has shown us how it treats genocidal states: there are only talks about tech innovations, handshakes, and the strengthening of ties with a regime that remains a champion of the mass murder of children. But here’s a concrete action you can take towards accountability.

International Law is No More, Fascism is Here: How Will You Choose to Operate in This Reality?

Fascism has never been a thing of the past; now, to disregard it means to disengage from reality. As international law has crumbled, Israel is still destroying Gaza, and masked agents are snatching people of the streets in the U.S., I invite you to ask yourself how you choose to show up in this reality.

As The U.S. Attacks Venezuela, Notice Who Bows Down to Empires and Spreads Their Propaganda

You would think we would be beyond cheering military aggression by empires. Yet be aware of this cheering, as well as of consciously erasing international law considerations in the coverage of recent U.S. attacks on Venezuela.

A Visual Summary of What Our Governments Have Allowed Israel to Do to International Law

When the UN premises are raided and the UN flag is replaced by the Israeli flag, it’s not even international news. It’s not a scandal. Because of the impunity our governments continue to generously gift to Israel (which in turn has rendered international law itself completely battered).

My Invitation to Rebuild a Media Company from Gaza

If you are looking for a very concrete opportunity to change someone’s life, here it is. I am inviting you to join me in rebuilding a media company that used to operate in Gaza. We don’t need that much — but we need you to be in.

How the European Broadcasting Union Just Gave Eurovision Fans an Opportunity to Show Some Spine (Thanks to Israel)

Israel was just allowed to compete at Eurovision in 2026. This shows nothing new about Europe’s literally unstoppable desire to maintain good relations with Israel. Now, the spotlight is on all the fans of Eurovision itself: we’ll see how unstoppable their love for this contest is, and whether it is above a genocide that has…

Don’t miss an update! Follow The Exploding Head

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.